Our students are empowered as leaders to learn and share traditional knowledge and teachings

Shekoli Swa kwe kon, Onkwehonwe ni:i Onʌyota’a·ka Tsi twa ka tuh ti. London Ontario Akta. Tyotsunit ne Hotinnoshoni ne yukats, kale’ Kaliwisaks ne yukyats Eileen Antone ne ah slo ni kek ne yukyats. Ano:wal ni wa ki ta lo tʌ.

Shekoli is a formal greeting in the Oneida language. Swakwekon includes everyone that is here. At this time, I bring greetings to you in the Onʌyota’a·ka language.

I am one of the Original people of Turtle Island (North America). I come from Onʌyota’a·ka known as Oneida First Nation of the Thames, near London Ontario, Canada. My name in the Longhouse is Tsyot súnit. Ka li wi saks is my research name and it means “She who gathers information.” An Elder who was a participant in my original thesis research gave this name to me. As we were talking and she was telling me about her journey through the residential school system she stopped and asked me what my ‘Indian’ name was. I had to tell her that I did not have an ‘Indian’ name. My mother and father former participants in the residential school system wanted to protect me from the strap and other harsh punishment that were applied to students heard speaking a traditional Aboriginal language. Eileen Antone is my English name. I am from the Turtle Clan.

The result of gathering information, has enabled me to come and share with you my story. Story telling has always a significant part of life in our community. During the long winter months story telling was one form of entertainment for young and old alike. My mother-law told this story of her childhood experience. She said, “that a long time ago there was an old man who went around our community telling stories in Onʌyota’a·ka“. She said when her parents would hear that he was coming to their place that night they would get ready. This was an exciting event she said, because he could make the stories come alive in her imagination. Her mother would make a big supper and have it all ready when the storyteller arrived. During supper, he would relate to them any news he heard in the community. After supper, while the adults continued to talk about the community news the children would clean the supper table, wash the dishes, sweep the floor and then bring their pillows and blankets and put them up close to the wood stove to keep warm while they listened to the stories the old man shared with them. The parents and children both related to the stories told. The old storyteller would spend the night with them and then the next day he would move on to the next house. Oral transmission of knowledge was our way of life. We learned what we heard and did what we had to make life comfortable and safe. Although orality continues in our communities, we also know that written stories assist in our ability to learn more about the various people and situations that have had a great impact on our lives.

As I observe the snow covering Mother Earth this morning, I know it is now time to tell my story as one of the Keepers of the Vision for the Sandy-Saulteaux Spiritual Centre.

I attended the Indian Day School system located in our Oneida community to grade six whereupon I was sent to Mt Elgin another Indian Day School in the Chippewa Community. As we did not have high school in the communities I was sent to London to attend one of their many secondary schools. This sytem was not for me so I left the Eurowestern educational structure of learning.

In 1975, I started my journey through the Post-Secondary Education where I was required to take a sociology course and that is where I was exposed to two significant Indigenous writers talking about the political and social conditions of Aboriginal people: one was Harold Cardinal and the other was Maria Campbell.

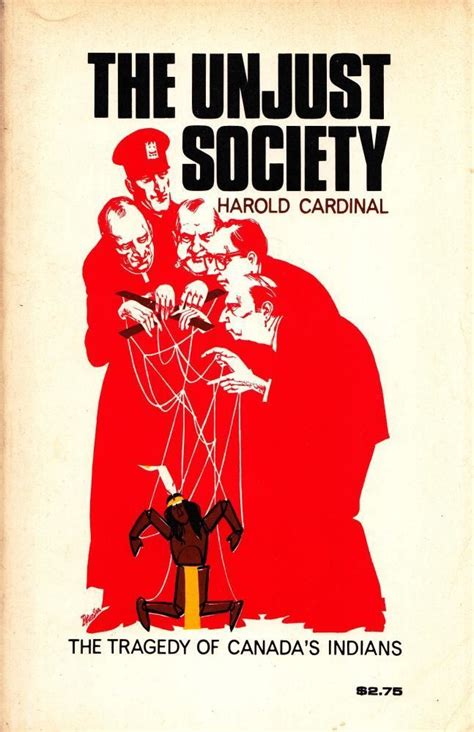

Through the exposure of these two Indigenous writers I became aware of the programme of extermination through assimilation policies of the government as explained by Harold Cardinal, a Cree writer, in his 1969 book called The Unjust Society -The Tragedy of Canada’s Indians.

Through the exposure of these two Indigenous writers I became aware of the programme of extermination through assimilation policies of the government as explained by Harold Cardinal, a Cree writer, in his 1969 book called The Unjust Society -The Tragedy of Canada’s Indians.

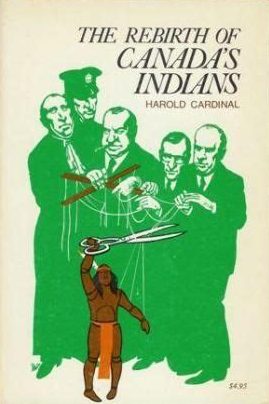

In 1977, Harold Cardinal also wrote another book called The Rebirth of Canada’s Indians, which was also a required reading for my sociology course.

My youngest daughter who was six at the time I was taking this class saw my book and picked it up and stared at the cover for a few minutes then she looked through the rest of the book. There were no more pictures, so she returned to the front cover again. After a while she looked up and said, “Look Mom, that Indian he don’t want to be a puppet anymore.” She was right. Puppets have no flesh, no spirit or soul and as chief Dan George states, “our greatest wound was not of the flesh but in spirit and in our souls. We were demoralized, confused and frightened.” (Chief Dan George p.19)

Although I was not aware of Native writers producing information about Native Peoples in Canada when I entered the Post-Secondary educational system our people were beginning to write about the plight of Native people in Canada which enabled us to contemplate how all Indigenous peoples were impacted by the offensive stereotypes associated with the words “Indian” and “half-breed” in the Canadian discourse.

It was during my journey through the Doctorate programme during the 1990s at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education that I was encouraged, by Dr. Hunt the Chair of the Multicultural teaching program, to learn about who I was as Native person. At this point in my journey I had to come to terms with the lack of knowledge I had about myself and other Native peoples in North America.

In my research, I encountered an article of a talk given by Lee Brown in 1986 at the Continental Indigenous Council, Tanana Valley Fairgrounds, Fairbanks, Alaska concerning North American Indian (Hopi) Prophecies. In this article, he talks about the spiritual awakening of Native people in the Americas.

“You’re going to see a time when the eagle will fly its highest in the night and it will land upon the moon.” … The Eagle landed on the moon, 1969. When that spaceship landed, they sent back the message, “The Eagle has landed.” Traditionally, Native people from clear up in the Inuit region, they have shared with us this prophecy, clear down to the Quechuas in South America. They shared with us that they have this prophecy. When they heard those first words, “The Eagle has landed,” they knew that was the start of a new time and a new power for Native people.

Many of our people awakened from their sleep and began telling their stories which has enabled a new generation of people to learn about and understand the situation that they grew up in and how it is now necessary to establish Indigenous space in the framework of the Canadian society including the Church.

I have had to go deep into the oppression of the educational struggles of the Aboriginal peoples. Why? To look for and raise up traditional knowledge and ways of being so that our people can create a place within this world where we can validate our own right within this present society. We can no longer dance to the strings of the puppet. We dance to the beat of the drum, the heartbeat of our nations and the strength of our people.

It is great to see from the reports given at the Keepers of the Vision Board meetings, at the Sandy-Saulteaux Spiritual Centre in Beauséjour, MB, the students are empowered as leaders to learn and share traditional knowledge and teachings from Indigenous communities as they develop their theology and spirituality. Our students are no longer bound by the oppression of assimilation as they bring teachings from their community Wisdom Keepers to the Sandy-Saulteaux Spiritual Centre.

References:

Brown, L., (1989)” North American Indian (Hopi) Prophecies” Talk Given at the Continental Indigenous Council, Tanana Valley Fairgrounds, Fairbanks, Alaska.

Cardinal, H., (1969). The Unjust Society. M.G. Hurtig Ltd.

Cardinal, H., (1977) The Rebirth of Canada’s Indians. M.G. Hurtig Ltd.

George, Chief Dan., (1969). “Our Sad Winter Has Passed.” I Am An Indian. Ed. Kent Gooderham. Dent. 17-19