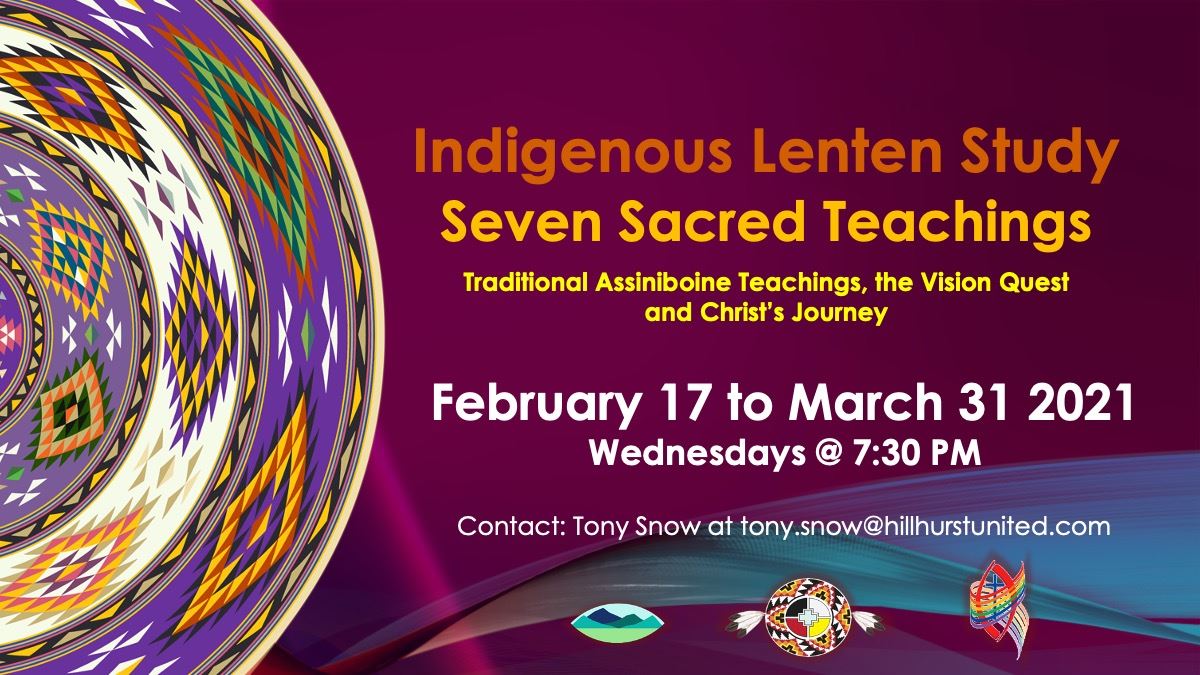

An Indigenous Lenten Study

Indigenous Lenten Series

Reflections on the 7 Sacred Teachings (7 Natural Laws) and the Vision Quest of the Assiniboine/Nakoda people.

Feb 17 – Mar 31, 2021

Online via Zoom: https://united-church.zoom.us/j/92373198977

During Lent 2020, the Urban Indigenous Circle began our exploration of Lent with an examination of the 7 Grandfather Teachings from the Anishinaabe tradition and its impact on other faith traditions, including the traditional narratives and spiritual expressions we see today in wellness and well-briety programs. The 7 Grandfather Teachings have also been used in addiction/rehabilitation/incarceration settings to bring knowledge and connection to those who may have been severed from their identity, their Elders, their community and their teachings. Through these teachings, a reconnection and understanding of who we are emerges. While many focus on the Anishinaabe teachings, other Indigenous peoples have similar expressions in their traditions as well.

This year, the Indigenous Lenten Series explores the 7 Virtues of Spirituality in the Assiniboine (Nakoda) Wisdom Tradition:

- Ahogichipabi – Live honorably, respectfully

- Wogidaîyâmi – Bravery/Courage

- Wîjaîchinabi – Fortitude

- Waahogipabi – A Peaceful Life, Humbleness, Humility

- Ogichichubi – Generosity

- Waushiginabi – Empathy

- Haram Wîchoharge womâkegya – Wisdom

Recordings of each session will be posted to YouTube:

- Session 1: Ahogichipabi (w/ Rev. Michael Blair) – https://youtu.be/HG7GJ9MDyts

- Session 2: Wogidaîyâmi ( w/ Dr. Gabrielle Lindstrom) – https://youtu.be/XmyTBOwakpI

- Session 3: Wîjaîchinabi (w/ Very Rev. Jordan Cantwell) – https://youtu.be/ODqtkiddOU4

- Session 4: Waahogipabi (w/ Moderator, Right Rev. Dr. Richard Bott) – https://youtu.be/88n9rssVGls

- Session 5: Ogichichubi – https://youtu.be/uQBv_Sifd20

- Session 6: Waushiginabi (w/ elder Alberta Billy) – https://youtu.be/Run29zmzdo0

- Session 7: Haram Wîchoharge Womâkegya (w/ Rev. John Snow Jr.) – https://youtu.be/brDZGaZOzlU

- Easter Sunday Service: https://youtu.be/L6bMSYKroQE

As we look to the lessons of each of these core virtues, we remember that Indigenous Teachings were never meant to be placed in isolation, studied in books or wrested from their ceremonial and cultural practice. They were and are part of our spiritual formation, a foundation of our practice. They are the words that came before all other words, meaning, they are an integral part of our understanding of self, community and how we interconnect with Creation. Our teachings inform our practice of building relationships with one another and with all things on Mother Earth through ceremony and prayer.

In this Series we set the Teachings upon the question: “Did not Jesus’ forty days and nights in the wilderness constitute a Vision Quest?” 1

Peter Jones (Kahkewaquonaby, Anishinaabe-Welsh missionary) pondered this question in his ongoing search for unity, balance and understanding between Christian beliefs and the teachings of our Indigenous ancestors. In this quest to make Christianity familiar and accessible to Indigenous people, early Indigenous missionaries like Jones drew on their intercultural skills to find relation between the visions, beliefs and practices of our people and the teachings of Christian missionaries to try to find a balance between traditions during those formative years. Indigenous missionaries working to bridge understandings with our cultural ways of knowing, is a large part of why we still maintain Indigenous Christian communities of faith and churches on many reserves in Canada today, not merely as a remnant of colonization, but as an attempt to balance the teachings of Indigenous people on our own terms with the offerings of the newcomers. That work continued in the 1970s with the rise of the Red Power movement and the re-integration of Indigenous spiritual practices in intercultural community settings like the Morley Indian Ecumenical Conference. The goal of conference organizers like Cherokee Anthropologist Bob Thomas and others was to restore the connection between faith, culture and spirituality, in order to restore ancient Indigenous traditions of ceremony, governance and social unity to reconnect people to who they are and what they believe. In this restoration of identity Indigenous people were invited to remember traditions with pride and a sense of belonging in their community and relationship to one another to deal with the pain of intergenerational trauma and lateral violence committed against each another, and to begin healing old wounds. This reintegration of the traditional teachings brings back the spirit of the people in a healing and healthy way, to take ownership of their destiny, restoring a wholeness to the present and setting a solid foundation for the future as people stepping back into the circle.

In the 1850s in what is now Alberta, at the foot of the Rocky Mountains, the Anishinaabe Methodist missionary Henry Bird Steinhauer was instrumental in bridging the understandings of Indigenous people with those of the newcomers. By bringing his perspective on Christianity into communities at Saddle Lake/Whitefish Lake, Maskwacis and Iyarhe Nakoda, Steinhauer formed some of the most robust dual faith systems in Indigenous communities that exist to this day. By not bringing a unilateral, dogmatic adherence to faith, but a doorway into a world seeking unity by bridging faiths through intercultural understanding and dialogue, Steinhauer was able to find greater unity (and strength) in both traditions. Today, 140 year later, these churches continue to exist, and their adherents continue the work of calling together the dual testaments of sharing and bilateral understanding that underscore the truth that these are all God’s teachings given to each group and each tradition, equally, and must be respected.

“If one understands the native religion of my people, it is not difficult to understand why so many of us embraced the gospel of Christianity. There was simply not that much difference between what we already believed and what the missionaries preached to us. What differences there were did not seem very important.”2 – Dr. Rev Chief John Snow, These Mountains Are Our Sacred Places.

For the Stoney Nakoda people, my father, the late Dr. Rev. Chief John Snow Sr, worked tirelessly to bring us into balance with non-Indigenous teachings, that we might bring out the best of both worlds, and to remind our Christian neighbors that their faith calls them to change and grow and develop in the same way we are called to evolve throughout our lives from child to youth to adult to Elder. For the Stoney people, this evolution of being was called the Vision Quest, and marked the time of spiritual formation and re-integration of new teachings and experiences into who we are moving forward. It defines our sense of self and purpose, and sets forth the lifelong commitment to community that guides our every action.

When the missionaries came, they were given the benefit of our traditional understanding of “people of God” who follow the teachings of Creator (Wakan Tanka) in an honest and forthright way. Our leading Elders and Medicine People were taught to trust people of God, because they were answerable to God. They held a place of honour because that was the tradition among my people. The words they spoke were taken as their truth, and influenced the Nations of Indigenous people to sign treaties; and the signatures these missionaries sit alongside those of our leaders, as well as the British monarchy’s representative as a commitment to this relationship covenant. It is only later as the true intentions of non-Indigenous missionaries began to be demonstrated, and our people entered into this Christian wilderness of deception and falsified intentions which we seek to remedy today with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Calls to Action and the Articles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, lifting up the relationship that should have been.

During this Lenten seasons, I think about my father’s journey into the Christian wilderness, a journey that taught him what faith meant to the newcomers and how it operated in their houses of worship. As part of this journey, he became the first ordained Indigenous minister in the United Church of Canada, and preached above all a balance of faith traditions that respected the sovereignty and agency of Indigenous people while participating in this ongoing project of community-building called Confederation in Canada. This sovereignty continues to maintain our distinct views, practices and traditional teachings that were handed down to us from the Creator. As we work with those of other faith traditions that are different from our own. His work reminds us that we are called to be our better selves: to work together in this existence called Creation, faults and challenges and all. My father’s vision was the vision that our ancestors shared when they signed Treaty: a vision that sought peaceful co-existence in the hope that the promises made would help our people enjoy a better tomorrow for the coming generations. 144 years after treaty signing, we continue to lift up their truth because we understand that the Creator gave us teachings and a wisdom tradition that governs our existence, and in order to be in full partnership in these lands, we must respect those teachings and their call to govern ourselves in respect and honour for the voices of our ancestors.

The Indigenous Lenten Series begins February 17, 2021 and is hosted by Tony Snow, Indigenous Lead for the Chinook Winds Region of the United Church of Canada. The Series is sponsored by the Chinook Winds Region and the Urban Indigenous Circle.

1) Smith, Donald. Sacred Feathers: The Reverend Peter Jones (Kahkewaquonaby) and the Mississauga Indians, Second Edition. 2nd ed., University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division, 2013.

2) Snow, Chief John. These Mountains Are Our Sacred Places: The Story of the Stoney People (Western Canadian Classics). 1st ed., Fifth House Publishers, 2005.